Novels

Photos

Interviews & Reviews

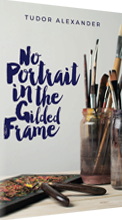

No Portrait in the Gilded Frame

Synopsis

An intelligent and captivating story about the emotional journeys we undertake and the corners of the heart we end up calling home, No Portrait in the Gilded Frame takes readers from Romania behind the Iron Curtain to the cosmopolitan cities of Israel and the lavish lifestyles of wealthy Southern California.

Centered around the life of Miriam Sommer, a gifted Romanian Jewish painter, the story opens in 1950s Romania and follows her as she experiences her first love, her first encounters with anti-Semitism, and her first betrayal at the hands of a lover.

Escaping heartbreak and searching for inspiration in new places, Miriam travels to Israel, where she meets immigrants and Israelis alike, learns to fend for herself, and starts new and complex relationships.

Her path from the wild girl in a backwater Romanian town to becoming a strong and willful woman fighting for her rights, takes the reader across decades and continents. With rich detail and finely crafted characters, No Portrait in the Gilded Frame is a story of exceptional emotional depth and beauty that will delight fans of literary fiction.

To purchase, please click on my author's page.

For additional information, please see my weekly blog and my activity on Goodreads.

Excerpt

My name is Miriam, or Miri to those close to me. Miri, a diminutive like the purr of a cat, like a squirrel’s dash through dry leaves. My surname is Sommer. It is pronounced with a z in the beginning, and it sounds foreign in Romania, the country where I was born.

I remember the balance of my early childhood in the mid-1950s: my mother and father; my older brother, Jacob, and younger sister, Adina; our three-room apartment in a building near the railway station; kids rolling hoops, jumping rope, or drawing with chalk on the sidewalk; the farmers’ market at the outskirts of town; the sky; the river; the ruins; and the traveling circus that visited at the end of each summer.

We lived in a town called Bistrița, in Northern Romania. My father, who worked for the government, told us that Bistrița, thirty thousand strong, was the capital of Năsăud County, a place crucial in the struggle of the proletariat.

Horse-drawn carriages waited for passengers in front of the railway station. The horses were scary to me, huge, their tails constantly swooshing, and the air near them smelled of dung.

The tall Evangelical church stood in Main Square. A few hundred yards from there, on Victoria Street, was my maternal grandparents’ apartment. We visited them often. Their apartment was old, spacious, and drafty; it stayed cool in the summer and had many dark places for me to hide in and disappear. It also had a fenced-in courtyard and a former stable.

A man and a woman lived in the former stable, I was told, because of the severe housing crisis. The woman’s name was Ileana. When I visited her she treated me to freshly fried pumpkin seeds generously salted. We spat the shells on a newspaper spread out on the dirt floor and drank lemonade from a pitcher. In the fall, Ileana got sacks of corn from the farm cooperative and let me pull the husks off the ears and play with the soft brown silk. The man, who I assumed was Ileana’s husband, had strong arms, wore torn undershirts, and was always tinkering. When he wasn’t tinkering, he was drinking plum brandy. All of us, my grandparents included, called him Uncle Tokachi, even though he was no uncle of ours. To begin with, he was much younger than my grandparents, perhaps younger than my parents, and, besides, he was Hungarian.

We were Jewish, although in those times we weren’t too vocal about it. Grandfather, especially, had this idea that being Jewish was a family secret. For a while I didn’t understand his fears too well, and I surmised that as far as family secrets went, they were always complicated. I also figured out that my grandfather didn’t like my father too much, but my mother loved him, and that was what mattered.

My grandparents’ parents came to Romania from a city called Lvov in Galicia in the 1900s in search of a better life. After the Soviets took over Lvov and, as my grandfather put it, liberated Romania at the end of World War II, his being originally from a territory now belonging to the Soviet Union could have gotten him a ticket straight to Siberia. Even I knew Siberia was a dreaded destination. To ensure this didn’t happen, my grandparents tried to disappear by settling in Bistrița, a sleepy town in the middle of nowhere, and by changing their last name from Levin, which was typical Jewish, to Levinescu, which sounded Romanian; then my grandfather joined the Communist Party. He was a doctor, for a time the chief cardiac surgeon for the County of Năsăud, and had to rush to the hospital each time there was an emergency. A black telephone mounted on a wall in my grandparents’ bedroom alerted him with its shrieking ring, inevitably in the evenings. The phone didn’t have a dial—just a cradle that supported the receiver—and to make a call you had to talk to an operator.

Whenever the phone rang, my grandmother answered. “Comrade Levinescu is resting,” she pleaded with the caller. “The doctor is taking a nap after a long day,” she argued in her slightly accented Romanian. “He has a weak heart as you know, and if you want him around, keep in mind he’s no longer a spring chicken.”

They wouldn’t listen and would send an ambulance to pick him up, or an army truck, or a horse-drawn carriage. A black Volga sedan stopped in front of the building once or twice, and often my grandfather would be gone for the night and the morning after.

Before he left, grandmother made sure he had his nitroglycerine tablets.